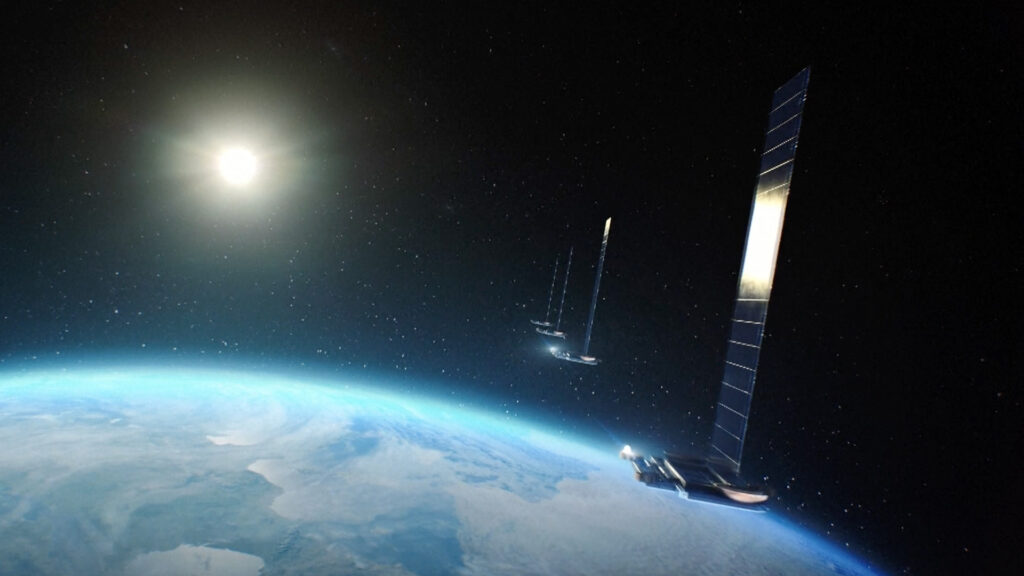

China just made a massive leap into the future of global connectivity—and it's not just another space launch. With multiple megaconstellations in motion, China is reshaping the satellite internet race, laying down the groundwork to challenge the dominance of SpaceX's Starlink.

The Big Launch: Spacesail Begins Its Journey

In August 2024, China launched the first 18 satellites of the “Spacesail” constellation from the Taiyuan Satellite Launch Center in Shanxi Province. It’s the first batch of what will eventually become a 15,000-satellite strong network designed to deliver high-speed, low-latency, ultra-reliable satellite broadband to users across the globe.

The satellites, weighing 300 kg each, were developed using a digitalized and modular design by a Shanghai aerospace company, which allows for efficient production. The launch vehicle? China's Long March-6A—a modern, medium-lift hybrid rocket.

What Is Spacesail?

Launched in 2023, Spacesail is being deployed in three phases:

- Phase 1 (2023–2025): 648 satellites for regional coverage.

- Phase 2 (2026–2027): Adds 648 more for full global coverage.

- Phase 3 (2028–2030): Expands to 15,000 satellites, offering mobile direct-connect and multi-service integration.

By the end of 2024 alone, 108 satellites are expected to be in orbit.

Not Just Spacesail: Guowang and Qianfan Are Also in Play

Spacesail isn’t China’s only move. The country is building two more massive constellations:

- Guowang (National Network): Announced in 2021 and operated by China SatNet, this network will consist of nearly 13,000 satellites. The first 10 were successfully launched on December 16, 2024, aboard a Long March 5B rocket. Unlike past launches, this one avoided the usual uncontrolled re-entry criticism by using an upper stage (YZ-2) to guide the satellites safely into orbit.

- Qianfan (Thousand Sails): Another 13,000-satellite megaconstellation. As of early 2025, 54 Qianfan satellites have already launched across three missions.

Both Guowang and Qianfan are designed to operate similarly to Starlink—offering low Earth orbit (LEO) internet connectivity, but managed directly by Chinese state-backed companies.

Why LEO Satellites Matter

Low Earth orbit satellites orbit closer to the Earth (typically 500–2,000 km), resulting in:

- Lower latency

- Faster communication speeds

- More efficient deployment

- Global and remote area coverage

These are essential features in today’s digital age, especially in rural and underserved regions where traditional broadband infrastructure is absent or unreliable.

Strategic Significance: More Than Just Fast Internet

This isn’t just a tech story—it’s a geopolitical one. Satellite internet is now seen as strategic infrastructure. The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) enforces a "use it or lose it" rule: countries must deploy satellite constellations within 7 years of declaration or risk losing orbital slots and frequencies.

China’s rapid deployment of these megaconstellations is a calculated move to claim orbital real estate before competitors do.

It’s also a race against time as other global players, including Amazon’s Project Kuiper and OneWeb (now owned by Eutelsat), push their own satellite internet projects forward.

Civilian Integration: Smartphones Go Direct to Satellite

With modern smartphones starting to support “direct-to-device” satellite connectivity (already seen in Apple’s iPhones and some Android devices), the value of satellite internet is skyrocketing. No more need for bulky satellite dishes or external equipment—users can connect straight to satellites for messaging and data in remote locations.

China’s satellite networks, including Spacesail, are expected to support these capabilities, opening up mass consumer use cases far beyond remote rural villages—think disaster zones, oceans, mountains, and even urban backup connectivity.

Laying the Foundation: Government-Backed Growth

China has made satellite internet a national priority:

- 2020: Satellite internet is added to China’s “new infrastructure” plan by the National Development and Reform Commission.

- 2021–2025: The 14th Five-Year Plan targets integration of GEO, MEO, and LEO satellite networks with terrestrial networks.

- 2023–2024: The Central Economic Work Conference and the 2024 Government Work Report name commercial aerospace, including satellite internet, as a strategic emerging industry.

- Cities like Beijing, Shanghai, and Chongqing have launched incentives to grow the aerospace and information industries.

On August 6, 2024, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology also proposed reforming satellite internet business access, aiming to support private telecom enterprises entering the sector.

The Global Matchup: Starlink vs. China’s Megaconstellations

Here’s how the players currently compare:

| Megaconstellation | Country | Planned Satellites | Launched So Far | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starlink | USA | 42,000+ | ~6,800 active | Live in many countries |

| Spacesail | China | 15,000 | 18 launched (108 by 2024) | Rolling out |

| Guowang | China | 12,992 | 10 launched | Early phase |

| Qianfan | China | 13,000 | 54 launched | Early phase |

| OneWeb | UK | 648 | 600+ launched | Operational |

| Project Kuiper | USA | 3,236 | Test satellites launched | Launches in 2025 |

Starlink still leads in size and global presence, but China is scaling fast. Unlike the commercial-first approach of SpaceX, China’s constellations are strategically coordinated by the government, giving them robust policy support and nationwide integration goals.

Final Thoughts: A Digital Space Race Has Begun

What we’re seeing now is a full-blown digital space race. While Starlink may have a head start, China is sprinting—with state funding, smart manufacturing, and a long-term vision. The launch of the Spacesail constellation, alongside Guowang and Qianfan, signals China’s intent to not only catch up—but possibly leap ahead.

With internet access increasingly tied to economic development, national security, and global influence, whoever controls the skies might just control the next era of the internet.